Ecological serial killers and Biodiversity loss (III).

- jijorquera

- Jun 2, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: May 25, 2025

Asesinos en serie ecológicos y pérdida de biodiversidad (III).

Many experts define the current and accelerating disappearance of species as the “sixth great extinction.” The substantial difference is that the previous extinctions had a natural origin, while the current one has human origin. The natural rate of extinction during the last two million years was one out of every 5,000 species in one hundred years (1). In contrast, only in vertebrates, the rate of extinction between the years 1900 and 2020 was about 117 times higher. The number of vertebrate species that became extinct during that time should have disappeared in 11,700 years, not in 120 years (2). This amount of time approximately coincides with the 150 years the Thylacine species lasted after British colonists arrived in Tasmania (see the previous post of this series).

An example of species depletion is the impact of fishing on the population of European eel (Anguila anguila). Today it is only 2% of what it was in 1980, just 40 years ago (3). Globally, fish catches increased about fivefold, from 19 to 94 million tons between 1950 and 2000, the years when “The Great Acceleration” started and the rate of impact of human activity upon the Earth's ecosystems and geology increased exponentially, in parallel to the growth of human population (4). I will further discuss the Great Acceleration in future posts.

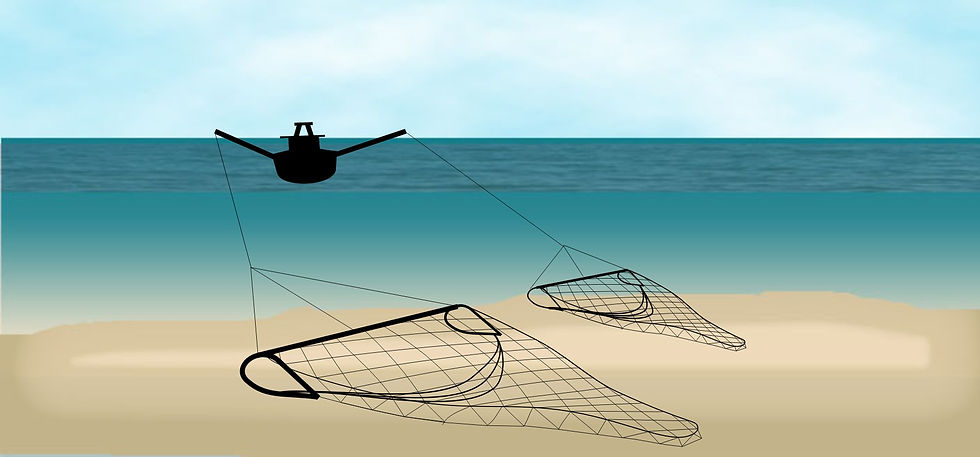

Deep-sea fishing employs nets dragged along the seabed, called bottom trawling. Bottom trawling's climate impact is not limited to fuel-use emissions; trawling also releases carbon from marine sediments. Seabed sediments are the world's largest carbon stores. As bottom trawlers drag weighted nets over the seabed, they disturb these carbon stores and release CO2 back into the ocean. These amounts of released CO2 are comparable to the amounts of gas generated globally either by aviation or by merchant shipping. The CO2 released contributes to ocean acidification, killing coral reefs and, indirectly, the fish that proliferate there. If we reduce the capacity of coral reefs to harbor life, we are compromising the future yield of fishing and this source of food for many human populations, not to mention whales, sea lions, and seals, among others. We are looking at another environmental vicious cycle. China, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, and Spain account for 64% of the high seas fish catch, worth U.S. $ 7.6 billion in 2014 (5).

Yuval Noah Harari, in his book Sapiens: A brief History of Mankind, coined the term "ecological serial killer" to describe our image in the eyes of other living beings (6). Since the departure of our species from Africa, this image has not improved—quite the opposite. It's not just about the ethical problem the toll of industrialized humans on the environment presents and the damage to nature that we will leave as heritage to future generations. We must also consider possible economic losses and the negative, unknown impact that failing to study each species before their extinction will have on the future of both human and environmental health, and on progress.

A high number of medicines’ active ingredients derive from biologically active substances discovered and initially obtained from animals or plants. In 1928, Alexander Fleming, a Scottish physician and microbiologist, discovered Penicillin in Petri dishes accidentally forgotten in his laboratory. Penicillin, originally produced by the fungus Penicillium notatum, became the first antibiotic, earning Fleming the Nobel Prize in 1945 (7). The number of lives saved by antibiotics is incalculable.

Among many other drugs originating from living beings, we can consider aspirin (derived from the bark of willow), anticoagulants (porcine heparin), and anticancer drugs, such as vincristine and vinblastine (initially obtained from plants in Madagascar). Rapamycin was first obtained from a humble soil bacterium on the island of Rapa Nui. It is used as an anticancer agent, but it also has immunomodulatory properties and even possible effects on human longevity. Metformin comes from the ancient herbal remedy French lilac and is used for the regulation of glucose metabolism by the large population of people with insulin resistance. Metformin might also affect human longevity (8).

Nature has developed medicines we have not discovered yet and materials that our engineers would like to find and then copy. We can talk about the strength and lightness of the fiber from the spider web or the resistance of the external skeleton of the ironclad beetle (Phloeodes diabolicum)—the size of a grain of rice (20 mm). No one would guess because of its size, but this beetle is capable of resisting forces 39,000 times its body weight. That force is equivalent to the weight of a car passing over it, as demonstrated by striving researchers whose names I do not want to remember, although the video was published on the website of the journal Science on October 21, 2020.

To view other posts in this web use this link. You may also be interested in the series of posts on the climate emergency.

More about biodiversity loss in future posts. You can also visit previous posts of this series:

Versión en español

Muchos expertos definen la actual desaparición acelerada de especies como la "sexta gran extinción". La gran diferencia es que las extinciones anteriores tuvieron un origen natural, mientras que la actual tiene origen humano. La tasa natural de extinción durante los últimos dos millones de años fue de una de entre 5.000 especies cada 100 años (1). En contraste, sólo en vertebrados, la tasa de extinción entre los años 1900 y 2020 fue aproximadamente 117 veces mayor. El número de especies de vertebrados que se extinguieron durante ese tiempo debería haber desaparecido en 11.700 años, no en 120 años (2). Esta cantidad de tiempo coincide aproximadamente con los 150 años que sobrevivió la especie de tilacino después de que los colonos británicos llegaron a Tasmania (ver publicación anterior de esta serie).

Un ejemplo de eliminación de especies es el impacto de la pesca en la población de anguila europea (Anguila anguila). Hoy queda a penas el 2% de las anguilas que había en 1980, hace sólo 40 años (3). Las capturas de pescado globales aumentaron casi cinco veces, de 19 a 94 millones de toneladas entre 1950 y 2000. Este período de tiempo coincide con La Gran Aceleración, décadas en las que la tasa de impacto de la actividad humana sobre los ecosistemas y la geología de la Tierra aumentó exponencialmente, en paralelo al crecimiento de la población humana (4). Discutiré más a fondo la Gran Aceleración en futuras publicaciones.

La pesca en alta mar emplea redes que son arrastradas a lo largo del fondo marino. El impacto climático de la pesca de arrastre no se limita a las emisiones del uso de combustible; La pesca de arrastre también libera carbono de los sedimentos marinos. Los sedimentos del fondo marino son las reservas de carbono más grandes del mundo. A medida que los barcos de pesca arrastran redes pesadas sobre el lecho marino, perturban estas reservas de carbono y liberan CO2 al océano. Estas cantidades de CO2 liberado son comparables a las cantidades de gas generadas a nivel mundial por la aviación o por la marina mercante. El CO2 liberado contribuye a la acidificación de los océanos, matando los arrecifes de coral e, indirectamente, los peces que proliferan allí. Si reducimos la capacidad de los arrecifes de coral para albergar vida, estamos comprometiendo el rendimiento futuro de la pesca como fuente de alimento para muchas poblaciones humanas, sin mencionar ballenas, leones marinos y focas, entre otros. Estamos ante otro círculo vicioso ambiental. China, Taiwán, Japón, Corea del Sur y España representan el 64% de la captura de peces en alta mar, por un valor de 7.600 millones de dólares de EE.UU. en 2014 (5).

Yuval Noah Harari, en su libro Sapiens: Una breve historia de la humanidad, acuñó el término "asesino en serie ecológico" para describir nuestra imagen a los ojos de otros seres vivos (6). Desde la salida de nuestra especie de África, esta imagen no ha mejorado, sino todo lo contrario. No se trata sólo del problema ético que presenta el daño al medio ambiente y a la naturaleza que dejaremos como patrimonio a las generaciones futuras. También debemos considerar las posibles pérdidas económicas y el impacto negativo y desconocido que no estudiar cada especie antes de su extinción tendrá en el futuro de la salud humana y ambiental, y en el progreso.

Un gran número de ingredientes activos de medicamentos proceden de sustancias biológicas obtenidas inicialmente de animales o plantas. En 1928, Alexander Fleming, un médico y microbiólogo escocés, descubrió la penicilina en placas de Petri que fueron olvidadas accidentalmente en su laboratorio. La penicilina, originalmente producida por el hongo Penicillium notatum, se convirtió en el primer antibiótico, lo que le valió a Fleming el Premio Nobel en 1945 (7). El número de vidas salvadas por los antibióticos es incalculable.

Entre muchos otros medicamentos procedentes de seres vivos, podemos considerar la aspirina (derivada de la corteza del sauce), anticoagulantes (heparina porcina) y medicamentos contra el cáncer, como la vincristina y la vinblastina (inicialmente obtenidas de plantas en Madagascar). La rapamicina se obtuvo por primera vez de una humilde bacteria del suelo en la isla de Rapa Nui. Se utiliza como agente anticancerígeno, pero también tiene propiedades inmunomoduladoras e incluso posibles efectos sobre la longevidad humana. La metformina proviene del antiguo remedio herbal Lila francesa y se utiliza para la regulación del metabolismo de la glucosa por la gran población de personas con resistencia a la insulina. La metformina también podría afectar la longevidad humana (8).

La naturaleza ha desarrollado no sólo medicamentos aún por descubrir, sino materiales que a nuestros ingenieros les gustaría copiar. Podemos hablar de la fuerza y ligereza de la fibra de la tela de araña o la resistencia del esqueleto externo del escarabajo acorazado (Phloeodes diabolicum), del tamaño de un grano de arroz (20 mm). Nadie lo adivinaría debido a su tamaño, pero este escarabajo es capaz de resistir fuerzas equivalentes a 39.000 veces su peso corporal. Esa fuerza es igual al peso de un automóvil que pase sobre él, como lo demostraron unos esforzados investigadores de cuyos nombres no quiero acordarme, aunque el video fue publicado en el sitio web de la revista Science el 21 de octubre de 2020.

Para ver otras publicaciones de esta web, use este enlace. Quizá pueda estar interesado en la serie de publicaciones sobre la emergencia climática.

Más sobre la pérdida de biodiversidad en futuras publicaciones. También puede visitar publicaciones anteriores de esta serie:

- Biodiversity loss (II), Homo Sapiens: una especie invasiva

Images / Imágenes

Serial killer / Asesino en serie. Author / Autor: John Tenniel. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jack-the-Ripper-The-Nemesis-of-Neglect-Punch-London-Charivari-cartoon-poem-1888-09-29.jpg. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Bottom trawling / Pesca de arrastre. Author / Autor: Ecomare/Oscar Bos. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ecomare_-_tekening_visserijtechniek_boomkorvisserij_(boomkorvisserij-schema-300dpi-ogb).jpg. CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Penicillium notatum. Author / Autor: Crulina 98. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Penicillium_notatum.jpg.

CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Phloeodes diabolicum. Author / Autor: Jesse Rorabaugh. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phloeodes_diabolicus.jpg. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

References / Referencias

1. Barnosky, A., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S. et al. Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature 471, 51–57 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09678.

2. Gerardo Ceballos, Paul R. Ehrlich, Peter H. Raven. Vertebrates on the brink as indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction. PNAS June 16, 2020 117 (24) 13596-13602; first published June 1, 2020. https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1922686117.

3. Kim Aarestrup et al. Oceanic Spawning Migration of the European Eel (Anguilla anguilla). Science 25 Sep 2009: Vol. 325, Issue 5948, pp. 1660. DOI: 10.1126/science.1178120.

4. David Christian. Origin Story: A Big History of Everything. Allen Lane, Penguin Random House UK, London, 2018.

5. Enric Sala et al., “The Economics of Fishing the High Seas,” Science Advances 4, no. 6 (June 2018); David Tickler, Jessica J. Meeuwig, Maria-Lourdes Palomares, Daniel Pauly, and Dirk Zeller, “Far from Home: Distance Patterns of Global Fishing Fleets,” Science Advances 4, no. 8 (August 2018), https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aar3279; Sala, E., Mayorga, J., Bradley, D. et al. Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature 592, 397–402 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03371-z.

6. Yuval N. Harari. Sapiens. A Brief History of Humankind. Random House UK. London, 2015.

7. Alexander Fleming. Nobel prize acceptance lecture. 1945. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1945/fleming/facts/. Accessed March 4, 2022.

8. Bill Gifford. Living to 120. Scientific American 315: 62-69, 2016.

Comments