Lands, Seas, and Biodiversity (IV)

- jijorquera

- Jun 9, 2023

- 12 min read

Updated: May 30, 2025

Pérdida de biodiversidad (IV). Tierra y mares

Populations within multiple species may be decreasing on a global scale, but this reduction does not occur equally in all the territories in which they are present. In some territories the populations grow, allowing us to target conservation efforts better (1). In this sense it is worth mentioning, without diminishing the value of other better-known nongovernmental organizations’ (NGOs) initiatives, such as those of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Greenpeace, the conservation activities developed by two NGOs—the Half-Earth Project of the E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation and the projects of Conservation International.

Humanity already covers most of the Earth’s land surface with its agriculture, settlements, and infrastructure (2). Agriculture has already transformed one half of the world’s habitable surface. As the population in Asia, and especially in Africa, continues to grow, this proportion will surely increase. We need that the yield of agriculture grows significantly, particularly in those regions (3). The land surface in its original state, untouched by human hands, comprises no more than 20% of the total. It is impossible to calculate the number of species we have lost forever. Soil is a mini ecosystem teeming with life. According to the Earth Institute at Columbia University, an acre of soil “may contain nine hundred pounds of earthworms, twenty-four hundred pounds of fungi, one thousand five hundred pounds of bacteria, one hundred thirty-three pounds of protozoa, eight hundred ninety pounds of arthropods and algae, and even sometimes small mammals … one grain of soil may hold one billion bacteria, of which only 5 percent have been discovered (4). And that does not account for the plant species present in the land before agriculture began.

The Half-Earth Project aims to restore and conserve half of the Earth's surface in its original state (5). This project is based on studies by Robert H. MacArthur, a mathematician and professor of biology at Princeton University, and by Edward O. Wilson, a biologist, naturalist, ecologist, and entomologist known for developing the field of sociobiology at the University of Harvard. Their research gave rise to the theory of island biogeography (6). MacArthur and Wilson showed that the number of species found on an island is determined by two factors: the effect of distance from the island to a continent and the effect of the island’s size. Therefore, a fundamental element for the conservation of species is the extension of the habitable surface where they can prosper. A smaller size is associated with an exponential decrease in the number of preserved species. This phenomenon is also applicable to isolated continental areas. It follows that increasing the area of conserved surface results in an exponential increase in the number of species protected from the risk of extinction. Accordingly, the calculations of scientists at the E. O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation indicate that by conserving and restoring 50% of the planet's surface, around 85% of the species still existing would survive. More recent studies also link the fight against climate change with the conservation of biodiversity. These studies confirm the importance of conserving and restoring up to 50% of the land’s surface, especially in fifty ecological zones affecting twenty countries (7,8).

More than 50% of humanity already lives in cities. In China, this figure reached 67% in 2024 (8b.) This fact, together with the slowing rate of global population increase, could represent an opportunity for the recovery of a part of the planet's surface to a state like its original condition, prior to human transformation of the land. Once again, it is urgent to act, given the accelerating pace of species extinction. To this end, a coalition of more than fifty countries has signed an agreement to promote the conservation of 30% of the land surface and oceans by the end of this decade (9).

On the other hand, Conservation International, in agreement with the authorities of several countries, has bought the rights to exploit several territories located between protected ecological reserves. These lands could otherwise have ended up deforested by paper manufacturers. Preservation of these areas permits creating biological corridors for the fauna, multiplying the conserved surface, and benefiting the original flora. Obviously, one of the most evident objectives to mitigate the increase in CO2 is to avoid cutting trees. Vegetation consumes this gas, decreasing its atmospheric concentration, and releases oxygen during photosynthesis. Conservation International is also involved in the care of marine areas, among other activities (10).

But we need to preserve and restore not only the land, but also the oceans. There may be well over two million unidentified species in the oceans. Here we can mention, among other initiatives, the ocean protection treaty establishing marine protected areas and the Ocean Census (11-13).

On March 4, 2023, the United Nations announced a historic treaty to protect biodiversity in international waters. The agreement sets up a legal process for establishing marine protected areas (MPAs), a key tool for protecting at least 30% of the ocean, which an intergovernmental convention recently set as a target for 2030. The high seas encompass the 60% of the oceans outside national waters. For decades, environmental groups have argued for protecting these waters from fishing, shipping, and other activities. Today, just 1% are highly protected, mostly in the Ross Sea in the Southern Ocean, where the Antarctic treaty created a protected area. The new treaty, which will enter into force once sixty nations have ratified it, would require a three-quarters vote of member countries to establish an MPA. That’s a much lower threshold than the unanimous approval required under the Antarctic treaty. Nations can opt out of an MPA—and continue to fish there, for example—but only a few reasons will be permissible, and any country opting out must offer measures to mitigate the harm. The treaty sets up a new forum for international deliberations, called a conference of the parties (COP), that will work with existing ocean authorities representing commercial interests, including fishing and seafloor mining (11). At present there are over 17,000 MPAs around the world, but they account for less than 7% of the ocean, and many MPAs still permit certain types of fishing. The scarcity of MPAs has led to the current situation, when 90% of fish populations are either overfished or fished to capacity (14).

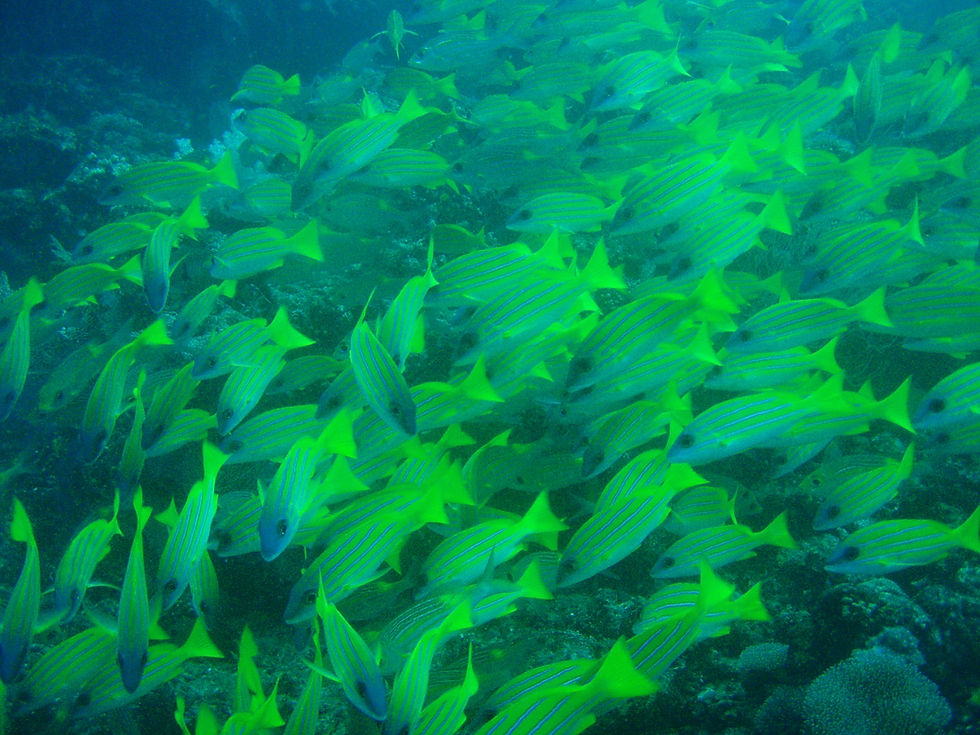

Maldives / Maldivas

If we were able to establish no-fish zones encompassing a 33% of the oceans, these areas could be sufficient to recover fish stocks and supply us with fish for the long term (14). The best locations for these MPAs would logically be the places where marine animals find it easiest to breed, such as coral and rocky reefs, underwater seamounts, and kelp forests, among others.

The Ocean census aims to identify 100,000 new marine species within ten years. With funding from the Nippon Foundation, Japan’s largest philanthropic organization, a U.K. marine science and conservation institute called Nekton will coordinate collections by ships, divers, submarines, and deep-sea robots. Ocean Census will make its data, along with 3D digital images of all new species, available to both researchers and the public (12,13).

Like soil, coral reefs are also mini ecosystems for microbial life. From 2016 to 2018, an international team of researchers studied ninety-nine reefs off thirty-two islands across the Pacific Ocean, home to 80% of the world’s corals. They sequenced DNA from more than 5,000 samples of three coral species, two fish species, and plankton. The team identified a half-billion kinds of microbes, mostly bacteria (15).

To view other posts in this web use this link. You may also be interested in the series of posts on the climate emergency.

More about biodiversity loss in future posts. You can also visit previous posts of this series:

Versión en español

Las poblaciones de múltiples especies pueden estar disminuyendo a escala global, pero esta reducción no ocurre por igual en todos los espacios en los que están presentes. En algunos territorios, las poblaciones crecen, y esto puede permitir orientar más fácilmente los esfuerzos de conservación (1). En este sentido, sin disminuir el valor de otras iniciativas de organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) más conocidas, como las del Fondo Mundial para la Naturaleza (WWF) y Greenpeace, vale la pena mencionar las actividades de conservación desarrolladas por dos ONG en particular: el Proyecto Half-Earth de la Fundación de Biodiversidad E. O. Wilson y los proyectos de Conservation International.

La humanidad ya cubre la mayor parte de la superficie terrestre con su agricultura, asentamientos e infraestructura (2). La mitad de la tierra habitable del mundo ya ha sido transformada para la agricultura. A medida que la población en Asia, y especialmente en África, continúe creciendo, esta proporción seguramente aumentará. Necesitamos que el rendimiento de la agricultura crezca significativamente, particularmente en esas regiones (3). La superficie terrestre en su estado original, intacta por manos humanas, comprende no más del 20% del total. Es imposible calcular la cantidad de especies que hemos perdido para siempre. El suelo es un mini-ecosistema lleno de vida. Según el Instituto de la Tierra de la Universidad de Columbia, un acre (4046,86 metros cuadrados) de suelo puede contener 400 kg de lombrices de tierra, 1.000 kg de hongos, 680 kg de bacterias, 60 kg de protozoos, 400 kg de artrópodos y algas, e incluso a veces pequeños mamíferos. Un grano de tierra puede contener mil millones de bacterias, de las cuales solo se ha descubierto el 5 % (4). Y eso no tiene en cuenta las especies de plantas presentes en la superficie antes de ser transformada para la agricultura.

El Proyecto Half-Earth (mitad de la Tierra) tiene como objetivo restaurar y conservar la mitad de la superficie de la Tierra en su estado original (5). Este proyecto se basa en los estudios de Robert H. MacArthur, matemático y profesor de biología en la Universidad de Princeton, y de Edward O. Wilson, biólogo, naturalista, ecólogo y entomólogo conocido por desarrollar el campo de la sociobiología en la Universidad de Harvard (6). MacArthur y Wilson demostraron que el número de especies encontradas en una isla está determinado por dos factores: el efecto de la distancia de la isla a un continente y el efecto del tamaño de la isla. Por ello, un elemento fundamental para la conservación de las especies es la extensión de la superficie habitable donde puedan prosperar. Un tamaño más pequeño se asocia con una disminución exponencial en el número de especies que se pueden mantener de manera estable. Este fenómeno también es aplicable a áreas continentales más o menos aisladas. De ello se deduce que el aumento de las áreas protegidas resulta en un aumento exponencial en el número de especies que pueden preservar del riesgo de extinción. En consecuencia, los cálculos de los científicos de la Fundación de Biodiversidad E. O. Wilson indican que al conservar y restaurar el 50% de la superficie del planeta, se mantendría alrededor del 85% de las especies aún existentes. Estudios más recientes también vinculan la lucha contra el cambio climático con la conservación de la biodiversidad. Estos estudios confirman la importancia de conservar y restaurar hasta el 50% de la superficie terrestre, especialmente en cincuenta zonas ecológicas que afectan a veinte países (7,8).

Más del 50% de la humanidad ya vive en ciudades. Este hecho, junto con la desaceleración del ritmo de aumento de la población mundial, podría representar una oportunidad para la recuperación de una parte de la superficie del planeta a un estado similar a su condición original, anterior a la transformación humana de la tierra. Una vez más, es urgente tomar medidas, dado el ritmo acelerado de extinción de especies. Con este fin, una coalición de más de 50 países ha firmado un acuerdo para promover la conservación del 30% de la superficie terrestre y los océanos para finales de esta década (9).

Por otro lado, Conservation International, de acuerdo con las autoridades de varios países, ha comprado los derechos para explotar varios territorios ubicados entre reservas ecológicas protegidas. De lo contrario, estas tierras podrían haber terminado deforestadas por los fabricantes de papel. La preservación de estas áreas permite crear corredores biológicos para la fauna, multiplicando la superficie protegida y beneficiando a la fauna y flora original. Obviamente, uno de los objetivos más evidentes para mitigar el aumento de CO2 es evitar la tala de árboles. La vegetación consume este gas, disminuyendo su concentración atmosférica, y libera oxígeno durante la fotosíntesis. Conservation International también participa en el cuidado de áreas marinas, entre otras actividades (10).

Pero necesitamos preservar y restaurar no sólo la superficie terrestre, sino también los océanos. Puede haber alrededor de 2 millones de especies aún por identificar en los mares de nuestro planeta. Aquí podemos mencionar, entre otras iniciativas, el tratado de protección de los océanos que establece áreas marinas protegidas y el censo de los océanos (Ocean Census) (11-13).

El 4 de marzo de 2023, las Naciones Unidas anunciaron un tratado histórico para proteger la biodiversidad en aguas internacionales. El acuerdo establece un proceso legal para establecer áreas marinas protegidas (AMPs), una herramienta clave para proteger al menos el 30% del océano, que una convención intergubernamental estableció recientemente como objetivo para 2030. La alta mar abarca el 60% de los océanos fuera de las aguas nacionales. Durante décadas, los grupos ambientalistas han abogado por proteger estas aguas de la pesca, el transporte marítimo y otras actividades. Hoy en día, solo el 1% está altamente protegido, principalmente en el Mar de Ross en el Océano Austral, donde se creó un área protegida bajo un tratado antártico. El nuevo tratado, que entrará en vigor una vez que 60 naciones lo hayan ratificado, requeriría un voto de tres cuartas partes de los países miembros para establecer un AMP. Ese es un umbral mucho más bajo que la aprobación unánime requerida por el previo tratado antártico. Las naciones pueden optar por no participar en una AMP, y continuar pescando allí, por ejemplo, pero sólo se permitirán algunas razones, y cualquier país que opte por no participar debe ofrecer medidas para mitigar el daño. El tratado establece un nuevo foro para las deliberaciones internacionales, denominado Conferencia de las Partes (COP), que trabajará con las autoridades oceánicas existentes que representan intereses comerciales, incluida la pesca y la minería de fondos marinos (11). En la actualidad hay más de 17.000 AMPs en todo el mundo, pero representan menos del 7% del océano, y en muchas AMPs todavía se permiten ciertos tipos de pesca. La escasez de AMPs ha llevado a la situación actual, en que el 90% de las poblaciones de peces están sobreexplotadas (14).

Si pudiéramos establecer zonas prohibidas para la pesca que abarcaran un 33 % de los océanos, estas zonas podrían ser suficientes para recuperar las poblaciones de peces y el suministro de pescado a largo plazo (13). Las mejores ubicaciones para estas AMPs serían lógicamente los lugares donde los animales marinos encuentran más fácil reproducirse, como los arrecifes de coral y rocosos, los montes submarinos y los bosques de algas marinas, entre otros.

El censo de océanos (Ocean Census) tiene como objetivo identificar 100.000 nuevas especies marinas en el plazo de diez años. Con fondos de la Fundación Nippon, la organización filantrópica más grande de Japón, un instituto de ciencia marina y conservación del Reino Unido llamado Nekton coordinará las colecciones de barcos, buzos, submarinos y robots de aguas profundas. Ocean Census pondrá sus datos, junto con imágenes digitales en 3D de todas las nuevas especies, a disposición tanto de los investigadores como del público (12,13).

Al igual que el suelo, los arrecifes de coral también son mini-ecosistemas para la vida microbiana. De 2016 a 2018, un equipo internacional de investigadores estudió 99 arrecifes de 32 islas en todo el Océano Pacífico, hogar del 80% de los corales del mundo. Secuenciaron ADN de más de 5.000 muestras de tres especies de coral, dos especies de peces y plancton. El equipo identificó 500 millones de tipos de microbios, principalmente bacterias (15).

Para ver otras publicaciones de esta web, use este enlace. Quizá pueda estar interesado en la serie de publicaciones sobre la emergencia climática.

Más sobre la pérdida de biodiversidad en futuras publicaciones. También puede visitar publicaciones anteriores de esta serie:

- Pérdida de biodiversidad (II), Homo Sapiens: una especie invasiva

Images / Imágenes

Edward Osborne Wilson. Author / Autor: Jim Harrison. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edward_O._Wilson,_2003_(cropped).jpg. CC BY 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons.

New York / Nueva York. Author / Autor: Dietmar Rabich.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_York_City_(New_York,_USA),_Empire_State_Building_--_2012_--_6440.jpg. Wikimedia Commons / “New York City (New York, USA), Empire State Building -- 2012 -- 6440” / CC BY-SA 4.0.

Maldives / Maldivas. Author / Autor: Juan I. Jorquera, 2008.

Coral reef in Maldives / Arrecife de coral en Maldivas. Author / Autor: Juan I. Jorquera, 2008.

References / Referencias

1. Leung, B., Hargreaves, A.L., Greenberg, D.A. et al. Clustered versus catastrophic global vertebrate declines. Nature 588, 267–271 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2920-6.

2. Erle C. Ellis. Ecology in an anthropogenic biosphere. Ecological Monographs. 85(3): 287-331, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-2274.1.

3. Vaclav Smil. How the World Really Works. A Scientist’s Guide to our Past, Present and Future. Penguin Random House UK. London, 2022.

4. Renee Cho, Joan Angus, Sarah Fecht, and Shaylee Packer, “Why Soil Matters,” State of the Planet, May 1, 2012, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2012/04/12/why-soil-matters/.

5. Half-Earth Project, 2021. https://www.half-earthproject.org/. Accessed June 30, 2021.

6. Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1967.

7. E. Dinerstein et al. A “Global Safety Net” to reverse biodiversity loss and stabilize Earth’s climate. Science Advances 04 Sep 2020: Vol. 6, no. 36, eabb2824. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abb2824.

8. Global safety net, 2021. https://www.globalsafetynet.app/. Accessed on July 16, 2021.

8b. Xuemei Bai and Peijun Shi. China’s urbanization at a turning point—challenges and opportunities. Science 388 (6747). DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3443.

9. The Guardian. More than 50 countries commit to protection of 30% of Earth's land and oceans. Accessed on July 16, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jan/11/50-countries-commit-to-protection-of-30-of-earths-land-and-oceans; Editorial. Sustainability at the crossroads. Nature 600 (7890): 569-570, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-021-03781-z.

10. Conservation International. https://www.conservation.org/. Accessed on July 16, 2021.

11. Erik Stokstad. Historic treaty could open the way to protecting 30% of the oceans. Science, March 7, 2023. DOI: 10.1126/science.adh4972.

https://www.science.org/content/article/historic-treaty-could-open-way-protecting-30-oceans. Accessed May 30, 2023.

12. Science news staff. News at a glance. The unknowns under the sea. Science, May 4, 2023. DOI: 10.1126/science.adi5510. https://www.science.org/content/article/news-glance-u-s-tallies-old-growth-forests-canadian-scientists-march-higher-pay. Accessed May 30, 2023.

13. Ocean census. https://oceancensus.org/. Accessed May 30, 2023.

14. David Attenborough. A Life on Our Planet. My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future. Ebury, Penguin Random House UK, London.

15. Galand, P.E., Ruscheweyh, HJ., Salazar, G. et al. Diversity of the Pacific Ocean coral reef microbiome. Nat Commun14, 3039 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-38500-x.

Comments